Guatemala, a country long facing major governmental corruptions and authoritarian influences, has recently gained a new advantage in the fight for a stronger and freer democracy with the election of its new president, Bernardo Arévalo. Since his election, Arévalo has fought for a more equal and just Guatemala. Unfortunately, many of his efforts have not achieved tremendous success.

The 2023 presidential election in Guatemala was rocked by several controversies, including the banning of three popular candidates by electoral authorities and multiple allegations of fraud and corruption. Reflecting widespread public discontent, the rate of voto nulo (nulled or spoiled votes) surpassed any individual candidate, reaching 17.3%. As no one candidate achieved more than 50% of the vote, the top two contenders advanced to a runoff election. One of these candidates, Sandra Torres, was an established political figure widely expected to attain victory, and the other was a dark horse candidate, Bernardo Arévalo. Torres is a conservative politician and former first lady who, as part of the National Unity of Hope party, has repeatedly won second place in the Guatemalan presidential elections. Arévalo, representing the Movimiento Semilla (Seed Movement) party, campaigned primarily on an anti-corruption platform in a country long plagued by corruption scandals, lack of judicial independence, and restrictions on the press. Because pre-election polling had never indicated that his campaign was popular among Guatemalans, Arévalo’s advancement to the runoff election was extremely surprising to Guatemalan political officials and journalists, triggering accusations of election fraud by his political opponents. Almost immediately, despite international condemnation, the Attorney General’s Office opened an investigation into the petition signatures obtained by Arévalo’s party. His party was later disbanded, though individual members were still allowed to take their seats in Congress.

The runoff election held on August 20, 2023, resulted in a decisive and unexpected victory for Arévalo. Despite the clear outcome, Sandra Torres immediately contested the election results, launching multiple accusations of electoral fraud. Roughly two weeks after the Tribuno Supremo Electoral initially declared Arévalo the winner, international condemnation of the fraud elections, including a statement from the U.S. ambassador, who called Arévalo’s victory a win for the defense of democracy, helped pacify the dispute. Ultimately, Arévalo was sworn in on schedule on January 15, 2024.

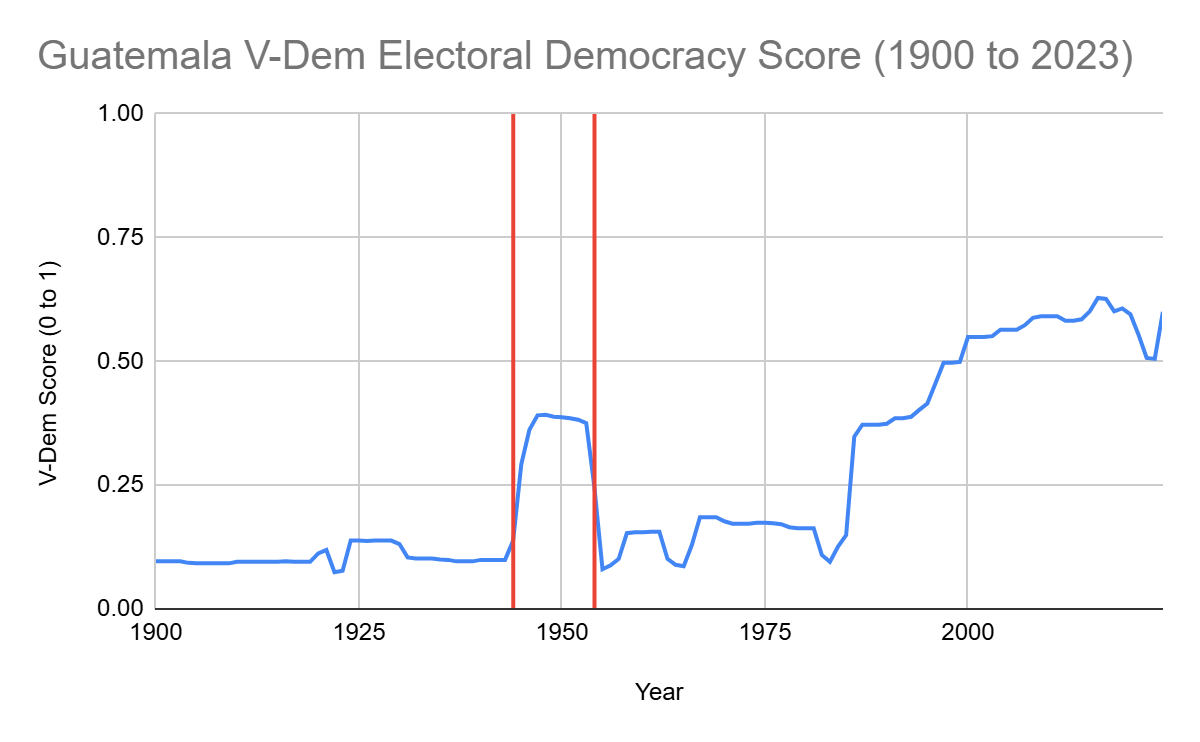

Following Arévalo’s electoral victory, considerable attention turned to the historical parallels between Arévalo and his father, Juan José Arévalo, who was the first democratically elected president of Guatemala. Juan José Arévalo presided over the first years of Guatemala’s period of democratic rule between 1945 and 1955, often referred to as ‘The 10 Years of Spring.’ Bernardo Arévalo’s presidential victory speech featured an apparent callback in which he spoke about “building a new spring.” Analysts have also closely examined the similarities between the challenges confronting Arévalo today and those faced by his father, including deep political divides and lasting authoritarian legacies. To contextualize this further, the graph below provides the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Score for Guatemala from 1900 to 2024, with the democratic period of ‘The 10 Years of Spring’ shown between the vertical red lines.

Although Guatemala’s democracy score rose significantly during this period, Juan José Arévalo’s administration never achieved the level of democratic consolidation seen in Guatemala's current democracy. Indeed, Juan José wrote that while democracy was the ultimate goal, the unstable political climate of the times permitted some undemocratic actions.

In contrast, his son, Bernardo Arévalo, has consistently relied on democratic means to address his corruption concerns, a laudable path that also cripples his success. For example, when Guatemalan prosecutor Rafael Curruchiche issued arrest warrants against Colombian politicians for their actions in an anti-corruption case through an agency backed by the UN, Arévalo could only publicly issue criticism. However, Arévalo has willingly utilized the power he does have, including his ability to appoint governors for each of the country’s departments. In the year and a half since Arévalo was sworn into office, he has rejected many potential appointees on the grounds of insufficient “public trust.” While it is clear that Arévalo is willing and eager to address corruption in Guatemala, democratic restrictions on his actions have resulted in only meager gains.

For example, in 2024, the Corruption Perception Index assigned Guatemala a score of 25 and a rank of 146 out of 180 countries, a two point gain from 2023. The index wrote that “after suffering long-term state capture by a corrupt elite, the country opened citizen participation channels and began digitalising public functions, to reduce opportunities for corruption.” Despite these incremental gains, major corruption scandals continue to surface. Most recently, the United Kingdom sanctioned prosecutor Ángel Arnoldo Pineda Ávila for his alleged involvement in “serious corruption,” accusing him of undermining investigations into Guatemalan elites and pursuing “meritless” legal actions against journalists and members of the press.

Despite President Arévalo’s stated commitment to press freedom, restrictive acts against the free press remain a prominent issue in Guatemala. Arévalo has been credited with fulfilling several of his campaign promises, including giving journalists more access to the inner workings of the government, holding more press conferences, allowing journalists in more events, and unblocking social media accounts. Arévalo also invited the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to visit the country for the first time since 2017. In its preliminary report, IACHR thanked Arévalo for his willingness to open the country again and acknowledged his promotion for human rights in Guatemala. However, the organization also noted that there is “deep-rooted hostility and resistance” to Arévalo, especially due to his challenges to the “political, economic, and military” elites seeking to maintain “structural impunity for crimes committed during the previous armed conflict as well as in current cases of corruption.”

In November 2024, President Arévalo signed the Declaration of Chapultepec, a document outlining ten principles of human rights. While Arévalo has said this signing is not solely a symbolic gesture, the document lacks binding enforcement. Once again, his personal commitment to press freedom has not been sufficient to prevent ongoing violations within Guatemala. In his remarks following the signing, Arévalo urged the Attorney General’s office to “end the arbitrary persecution of journalists,” yet such appeals have yielded little concrete action thus far. One of the most prominent cases involves José Rubén Zamora, founder of El Periódico, an important newspaper in Guatemala. After publishing an investigation into governmental corruption, Zamora was arrested on July 29, 2022, before Arévalo’s election to the presidency, and the newspaper was forced to close. Although Zamora has since been released, he was detained for an extended period, and continues to face ongoing legal battles. Additionally, a judge received threats while handling the case after expressing reservations on upholding Zamora’s conviction. Lastly, a significant number of Guatemalan journalists remain in exile. Despite Arévalo’s expressions of sympathy, conditions in Guatemala continue to pose severe risks for members of the press.

Anti-corruption efforts clearly continue to be a priority for Arévalo’s administration. As recently as September 29, 2025, Arévalo met with U.S. officials to discuss anti-corruption efforts and continued American support. However, in the absence of substantial policy action or visible progress, public confidence in his presidency is likely to continue to erode. Many Guatemalans are increasingly recognizing that there is no immediate or “magic” solution to the country’s deeply entrenched corruption and governance challenges.

.svg)